••••

Kimono Mochi

'In Kyoto, where the affectionate local dialect for kimono is obebe, women speak of the enviable state of being obebe mochi; having lots of kimono.'

Liza Dalby: Geisha

••••

Stored here is a list of my eclectic kimono collection, which numbers well over two hundred. It encompasses everything from Edo to present day, from hand spun and woven to machine washable, from kinsha silk to cotton. If I love it, it's in here. And it's here because I hope you'll love it too.

••••

Please navigate between pages by clicking on the small three-bar icon at the top left of this page - other pages and subjects will appear.

••••

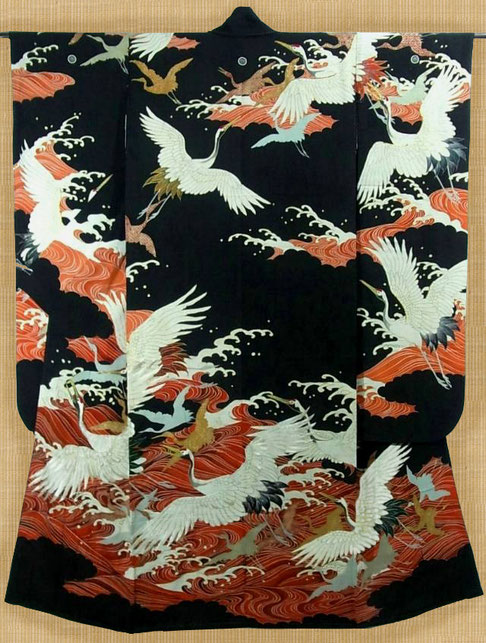

Furisode

Meiji bride's hon-furisode with full-body yuzen, kinkoma, and Shishu. Length 62"

Wedding furisode of this type (this is an hon-furisode, or O-furisode, for a bride rather than a more traditional kakeshita, a plain kimono designed to always be worn under a second layer such as a padded and embroidered uchikake, or a damask Shinto shiromuku) are often richly decorated with every possible technique. This is a very soft chirimen silk with no loss of color and clean, clear yuzen work (a time consuming and highly skilled technique which creates holdout areas within a background colour which are then hand-painted into). Almost all of the kinkoma (gold couching) had to be reattached, and a small tear close to the rear hem was professionally repaired at some point (they're generally in one of two places; to the front a few inches up, where the foot may trap the kimono when standing, and at the same height to the rear, where stepping back into a trailing hem is always risky!).

There's also some fine hand embroidery of a type known as hira-nui worked exclusively on the cranes themselves, to give them an almost three-dimensional quality which lifts each individual feather from the background. Because cranes are believed to mate for life they're considered auspicious symbols, and grace most wedding kimono.

Both hem and sleeves have midweight fukiwata (padding). The hakkake is also full yuzen, and of course given its age, this kimono has a deep red lining which is considered lucky ( in warding off evil spirits ) for the bride. Sourced in Osaka, Japan.

Antique chirimen silk homongi with yuzen and embroidery. Length: 59.5"

This is a much older piece than the one above, as evidenced by the fact that it is hand spun and hand woven, with the softness of feel and drape which this encompasses. The placement and choice of the mirror design means that it could have originally been a wedding hon-furisode which had its sleeves shortened to a married woman's length after its wedding debut, as was generally done at the time. In this case the length of the sleeves, as well as the mirror design, locks the alteration down to early Taisho at the very latest.

The quality and subtlety of the hand painting on the yuzen areas is outstanding, particularly the turtles and cranes, as seen

below.

It has neither surihaku (gold size) work nor kinkoma (gold couching), but hundreds of tiny, delicate repeat stitches of gold thread

scattered throughout the design. These are incredibly small; you can just barely make them out on the bark of the tree, and again to pick out detail in the turtle's shell. They would have given the tiniest subtle glimmer when

worn. There's also extensive hira-nui embroidery (not shown here) to pick out two cranes on the chest of the kimono. This unusual addition of a design to the front of the chest on a

kimono with no other decoration save to the suso (hem area) further hints at this kimono's bridal origins, and though it could be easily mistaken for an iro-tomesode, this addition of a design

other than at the suso drops it into a hybrid category of tomesode/homongi in terms of occasion suitability. Time, Place, Occasion is a whole area of learning to wear kimono, with specific types

of kimono suitable for very specific occasions. Tomesode are very formal kimono, with black kuro-tomesode being the pinnacle of formality for a married woman, limiting their wearing to family

weddings and the equivalent of black-tie occasions. To have what was considered a high-end homongi would enable the wearer to dress this kimono up or down with suitable obi and kitsuke (extras

such as obi-age, obi-jime, eri, etc), making it suitable for a much wider range of occasions.

The entire kimono has silk floss (not the more common cotton or kapok seed fiber) batting which was too fine for the hand weave and so had threaded itself through the outer weave a single, fine, floss-thread at a time, rendering the entire surface hairy and bobbled, like an old jumper. Although they look awful in this condition, they are restorable with an investment of time and patience, requiring opening an internal seam to each panel, to enable the restorer to slide their hand within and manually free up the batting a few floss-threads at a time, cutting any bobbling on the outside the surface to free the floss as they go.

This kimono has excellent, intense color to yuzen and body with no fading (a rarity for blue kimono)--probably due to little wear, as

the batting appears to have failed very early in its life and so it was consigned to a dark chest and left alone. The hakkake is also full yuzen, and

in this case, the upper lining (doura) is cream hand-woven habutae.

Tomesode are a huge category, and so have a page of their own on this site. Just go the very top of any page and click on the small three-bar icon at the top left; a menu will appear listing other pages, each containing different types of kimono.

Vintage kinsha chu-furisode with embroidery, couchwork and surihaku. Length: 62.5"

Furisode, probably the Western concept of what a Japanese kimono should look like, are of course specifically for young, unmarried women, and these days rarely seen outside of Graduation, New Year and Seijin No Hi (Coming of Age) ceremonies. Most modern furisode tend to be on the over-effusive side for my rather toned-down tastes, so I find I naturally gravitate towards older, more subdued kimono. In fact, this is one of the most brightly colored that I own. This one is probably mid Showa, when kimono were already disappearing from everyday life, and has chu sleeves--mid-length, rather than the more formal ankle-length--a type of furisode that was beginning to die out as only the more formal full-length sleeve furisode were required. There's a large amount of embroidery work, with surihaku (gold size work) applied throughout the kimono, though its subtlety means that it's only visible close up. To me, this is a perfect example of of its time, bridging the divide between older, more artistic pieces and modern Western influence, with the design and colors having a slightly 'harsh' feel to them, by comparison to older pieces. Sourced from Osaka, Japan

Antique Meiji-era rinzu kinsha silk furisode with yuzen work. Length: 62.5"

It's interesting to compare this furisode with the more contemporary one above. In this case, despite their having been long gone, the remnants of the sumptuary laws which had dictated that designs were kept to the bottom of the skirt and sleeves--one of the factors which turned attention to the less restricted obi, leading in part to its increasing dominance in the ensemble--were still influencing design. Despite, or perhaps because of such constraints, as a complete piece the design is infinitely more subtle, with a more restricted and harmonious color palette. Synthetic aniline dyes were available at this time but unlike the chu-furisode above ,they still largely tried to emulate the subtlety of their natural plant-based predecessors, though this would soon change. It's not possible to see at this distance, but the silk itself is also rinzu (silk with a design woven in, like European damask) of yabane; arrow flights.

Though it pre-dates it, this is close in style to the blue iro-tomesode above, and because this kimono

has retained its original sleeve length, you can see how the sleeves of the blue iro-tomesode might have been shortened

without compromise of the overall design. By comparison to the contemporary furisode above, you can also see the older mirror style design, before it transmuted to what is today the

near-universal maemigoro irregular left-to right bias (the highest and most effusive point of the skirt design is always to the left front, which is the most visible, and over the back of the

right shoulder, to balance it visually).

This furisode has an incredibly delicate freehand-painted design (yuzen-moyo technique) of multiple flowers set within larger yuzen holdout areas. Padded throughout, with fukiwata (cotton batting to hemline). Sourced from Osaka, Japan.

Bridal hon-furisode with yuzen, embroidery and kinkoma. Length: 65"

Another bridal (trailing) hon-furisode, this one a little more recent than the Meiji kakeshita at the top of the page, though you can see the similarities in

design, and in the color palette. The sprayed resist ground from black to green-gray to peach identify this as slightly later, though the dyes are in the main still plant-based (or

mimicking such) rather than the more contemporary man-made pigments--though again, synthetic dyes were widely used from the 1850's onwards. A traditional design of bridal carriage and auspicious

flowers single this out as a bridal kimono, as does the length (designed to trail) in comparison to the sleeves. These would have been tailored to come to ankle-length, giving an indication of

how much length was left in the main body, allowing for a trailing hemline.

This piece has a lot of hira-nui hand embroidery, which is a type of satin stitch, and unusually for a bridal kimono, the mon themselves are embroidered in kinkoma (gold-wrapped thread) in traditional koma-nui, a couching stitch. The yuzen is almost full coverage, and as is typical of the era the lining is red, a tradition to ward off evil spirits. Padded throughout, with fukiwata (cotton batting to hem, to encourage the trailing kimono to spread pleasingly as the wearer walked ). Sourced from Tondabayashi City, Osaka, Japan.

Don't forget you can navigate between pages by clicking on the small blue three-bar icon at the very top left of this page - other pages and subjects will appear.

Young Boy's Edo-era Kimono. Length: 36"

An absolutely wonderful old Edo-era boy's kimono in very soft hand spun and hand woven silk, with full-body batting (padding).

Note that the same sumptuary laws which limited designs to the hemline of kimono for adults were also in place for children--though by the mid-eighteen-hundreds it was an adherence to tradition

rather than law, particularly on the part of the generally more conservative Samurai families. Despite the long sleeve length (boys wore the same furisode-length sleeves as girls; the word

furisode is simply a combination of furi: fluttering and sode: sleeve), this kimono can be singled out as a boy's due to the carp motif, harking to the commonly-held belief that carp exemplify

the desirable virtues of vigor, perseverance, and strength of purpose, translating to an aspiration that one's son would be equally willing to struggle against adversity.

The entire design is beautifully hand-painted and the colors very bright, though the silk itself is delicate and has failed a little around the neckline due to age

(that's not the red thread you can see around the centre mon; those threads are a kind of talisman to ward off evil, by breaking the design to centre-back in a kimono that, unlike an adult's, had

no centre-back fabric seam). The sad fact is that there's little that can be done to slow down the decline of silk, which is a natural product, save to keep it away from light and in a steady

atmosphere with minimum folds. Although light has long been considered the main ageing culprit for silk (and is still responsible for fading of dyestuff and the damaging breakdown of mordants),

recent tests have pointed the finger squarely at changing humidity, with UV light coming close behind, as well as processing such as infamous mineral salt mordants, which are again accelerated by

humidity levels. Rapid temperature swings between highs and lows hugely influence humidity, causing expansion and contraction in the silk which is particularly damaging.

This kimono has samurai mon and a full red lining, with a secondary partial hiyoku to sleeves and collar in black. The kimono itself is a very dark green-grey. Probably made for kodomo no hi (boy's day) or sichi-go-san (seven-five-three) festival. Sourced in Kyoto, Japan.

I'm on Etsy!

I've opened a store on Etsy selling vintage kimono and kimono wares from my collection, as well as Japanese cards and gifts handmade by myself from vintage kimono silk. Click on the image above and come take a peek!

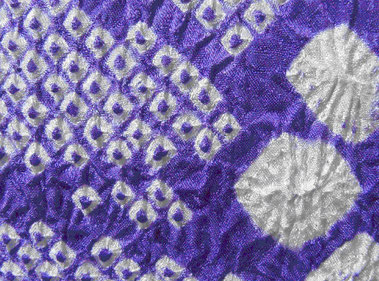

Contemporary furisode, full shibori. Length: 65"

At the other end of the time scale is a full shibori furisode whose length is a good indicator of its contemporary status, as Japanese women grow taller every year.

This one is of interest in that, though the underlying design has a large curve just visible moving from left front panel to right shoulder in the traditional manner, modern design steps away

from established rules occasionally and the actual color of this piece is in horizontal bars rather than the widely observed maemigoro (left-front) bias. More than any other type of design

shibori tends to blur such design rules, and is as popular today as it it has always been.

Shibori itself is an ultra-fine tie-dye technique generally (but not always) consisting of thousands of tiny individually cotton-wrapped or stitched areas tight enough to resist any subsequent dying. When combined, this can create a highly-textured and complex image. Purists often say that shibori should be a single, all-over texture with no visible design, but almost since its creation (save for a brief period in which it was banned entirely by the Shogunate, due to its opulent, time-consuming nature), it has been used to create intricate patterns of incredible dynamic exuberance. Sourced in Osaka, Japan.

Vintage furisode, full shibori. Length: 62"

Another full shibori furisode, this one from a little earlier in the Showa period. This time, the more traditional maemegoro left front to right shoulder pattern

bias can be seen, though the amount of decoration on this chu-furisode (mid-length sleeve) make it a little hard to identify. But you need only look for a few seconds to discern a clear

area to the right of the main body, partially covered by the sleeve. To a trained Japanese eye, this would be instantly read and understood. This design, with its multiple colors and

vibrant folding fan pattern, is intended for a younger wearer--or perhaps simply a more extrovert one, daring enough to carry this off.

In this instance, unusually, there's no horizontal seam which often occurs sewn to the back of the waist (there's generally no corresponding seam made to the front of the kimono unless the wearer is very short) and is used to fine-tune the pattern where side seams meet, as well as to adjust the height of a kimono to the wearer, within a few inches. The ohasori, a fold made in the kimono at the waist when donning it, and visible below the obi line when worn, is used for finer length adjustments. The reason that this seam is often absent in shibori pieces is simple; the fine crinkling caused by tie-dying over an entire bolt actually shortens the bolt, and though the shibori is relaxed using steam before sewing, the textured surface is a desirable trait and so is very much in evidence, thus reducing the bolt length. It's also often said that shibori is, by its nature, slightly stretchy, and so the waist seam which supposedly protects the kimono from accidental rips (it's believed that the stitching will break before the fabric rips) is unnecessary. Either way, the absence of the sewn waist seam enables the viewer to appreciate the flow of the design as originally laid on the fabric. Sourced in Osaka, Japan..

There are several more examples of different shibori techniques on different pages of this site; just go to the the very top of this page and click on the small blue three-bar icon at the top left - a menu will appear listing other pages showing different types of kimono.

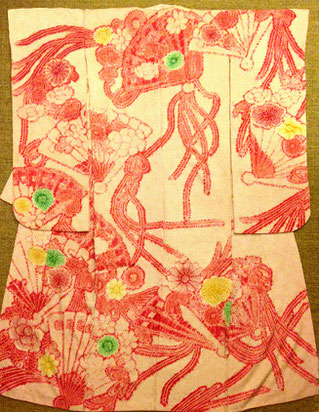

Antique chirimen silk wedding hon-furisode with yuzen Length: 67.5"

Another Showa era wedding furisode, one of two I own which sport ougi/sensu (folding fan) designs. Of the two, this one has a far

higher amount of yuzen work and is also slightly older, and easier to lock down to an early Showa pre-WWII furisode. As such it has only a small amount of surihaku and no kinkoma, but does have a

good amount of hand embroidery in the form of hira-nui and sagara-nui to the yuzen-work flowers. This one also has more yuzen detail to the shoulders of the kimono, both front and back, as well

as five kamon.

The patterns on the fans, as well as the fukiwata, give this piece away as a wedding furisode rather than a black hon-furisode

(trailing furisode), as beside a mass of flowers both real and imaginary, once again it sports those flying crane which mate for life, as well as goshoguruma (a type of ox-cart used mostly

by samurai women, as well as to transport a bride).

By this time it was becoming less common for wedding furisode to have their sleeves shortened for use as tomesode after marriage, and so the design on the sleeves began to creep up to a point where shortening them without still showing yuzen work (something which doesn't occur on a kuro-tomesode) was impossible. The yuzen work over the shoulders--a place which would never have any design on a formal tomesode--also means that this furisode managed to keep its fluttering sleeves.

Here's a picture of the same kimono fitted onto a mannequin, to see how the design works three-dimensionally, which is always very

different. You can see how the placement of the design is heavier on the over-wrapped upper left shoulder, to balance the colourful lower skirt as it wraps over to the right. It's also

interesting to note how high the skirt design comes, and just how little of the black background is visible when worn, as opposed to the traditional back-view for display. Here, it's shown with a

saganishiki (sewn fabric) obijime and a

full-shibori obiage, wrapped rather than knotted, in the furisode style. Sourced in

Osaka, Japan.

Antique chirimen silk furisode with yuzen Length: 64"

Back to more generic furisode now, since though this one looks very much like a wedding furisode, the motifs of boats and flowers are

more general, indicating it's a single woman's furisode rather than a wedding one. The placement of the pattern on the sleeves means that it would also be difficult to eventually shorten them to

make a married woman's iro-tomesode (iro before tomesode simply indicates

that it is a coloured tomesode, as opposed to a black-background kuro-tomesode. No

matter the number of mon, this sets the iro-tomesode slightly lower in ranking than a kuro-tomesode). Further design over the shoulders also excludes this kimono from being altered into an iro-tomesode.

The kinsha silk used in this piece is of particularly high quality, and the sleeves long at 112cm.

The quality of this piece is also evidenced in the fact that not only is the hakkake completed with yuzen designs, but also the inside of the sleeves, 'lest the onlooker gets a glimpse of the interior as they flutter. The hira-nui embroidery to all panels is also very fine quality. This kimono does suffer from that common failure of its time though, in that a little of the scarlet dye from the classic red lining has begun to transfer to the outer silk just around the mon, where the silk is particularly vulnerable after rice-paste is used to hold out the mon area. It's still a lovely piece in a classic mustard colour, though. Sourced in Osaka, Japan.

Vintage furisode with yuzen and shishu Length: 62.5"

Like the furisode above, though this one looks very much like a wedding furisode, the more general motifs indicate a more general

furisode. It does have five mon, but since the mon are embroidered and not dyed, this places it slightly lower down on the formality scale than its dyed-mon cousin above.

The rinzu is very soft and of a high quality, and both the outer and the hakkake have yuzen work to them, with the outer kimono having hand-embroidered accents.

Although the rinzu (damask) ground mimics beni, a safflower-petal derived plant dye, the general motifs seem to place it towards the middle of the Taisho era. This can be seen from the close-up of the flowers, which have a very definite simplification to them that really only came into being in the fifties. So this is likely a transitional fifties furisode with some traditional elements, rather than the antique pre-WWII kimono that it was sold as. The embroidered mon, which tended to come in towards the mid-Taisho period, also push it a little more firmly to that era. Sourced in Osaka, Japan.

Vintage ko-furisode with yuzen. Length: 60"

Something very different now. This is a rinzu (figured) mon kinsha silk kimono dating somewhere between late Taisho or very early Showa, so around 1910 to 1925. A lot was happening at this time, with outside influences being widely adopted and adapted to Japanese life on the back of a boom to the economy. In the wafuku industry, aside from mechanised spinning and weaving of slubbed silk which had previously been impossible save by hand, synthetic dyes were also coming into their own, for the first time offering bright and varied colours rather than trying to mimic older plant dyes. All this coincided with the appearance of Western-style department stores in major cities, which sold pre-made kimono ready to wear--a concept previously unheard of for wafuku. Emulating Western traditions, new ranges were brought out twice yearly, meaning that such kimono had a short useage life in terms of their fashionable appeal to young Japanese women who for the first time were beginning to move out of the home sphere, with the booming economy giving them the disposable income which fed the process.

Such kimono were often consigned to a chest after only a few season's wear, meaning that many have survived quite well. This is an unmarried ko-furisode, the most informal of its class, as evidenced by the shortness of its sleeves (ko literally means short) and the non-matching komon-style design--more formal kimono would match their design over seams, as you can see on the homongi page.

Its casual status is also indicated by the fact that it has no mon (ready to wear kimono don't always lack family kamon; they can be

left at a department store to be embroidered by the store's specialist, or there can even be a pre-held-out section on more expensive kimono, ready for a screen-printed kamon to be applied, again

by a specialist). It does, however, have a full hiyoku, with the hakkake and sleeve accents in mint green, and the hiyoku's uwamae (body skirt) and fure (inner sleeves) in traditional

scarlet.

This type of design would drop easily into the Taisho-modo or Taisho-roman (a shortening of Taisho romantic) style, and today many Taisho-roman or kimono-hime enthusiasts would team it with Western-style Victorian button-up boots, and dress it with bags, gloves, lace, shawls and hats from Western 1920's styles, in those fantastic fusions of modern and vintage. Sourced in Osaka, Japan

Hon-furisode with yuzen, kinkoma and surihaku Length: 71"

Back to a more formal furisode now. The soft peach background of this rinzu silk never photographs well for some reason, looking a little grubby rather than its true delicate hue, which is a pity.

The motifs on each of the fans make me suspect that this is a wedding furisode, as aside from general flowers such as plum blossom,

cherry blossom and chrysanthemum, there are cranes and kikko (tortoise shell), both of which generally indicate a wedding. The length too, at an impressive 71", also indicates that this kimono

was made to be hikizuri--trailing its skirt, as only brides, dancers and geisha do. It is an interesting one though, as it would be very easy to miss the signs--I didn't notice them when I bought

it, assuming that the mix of flowers was a pan-seasonal in design. It was only on closer inspection that I spotted them.

There's also a lot of kinkoma and surihaku on this piece, outlining each of the fans and some of the detailing within them, to the

front panel. It's hard to see because of the subtlety of the white against the peach background, but this is of course a five-mon kimono. There's also a muted red yuzen hiyoku to add the

effect of a second kimono, and both kimono and hiyoku fukiwata are lightly padded to help the trailing kimono spread pleasingly when worn. Sourced in Kyoto,

Japan.

Hon-furisode with yuzen, kinkoma and surihaku Length: 61"

The second formal furisode with a design of ougi (fans) quite different to the black Showa-era one. Being black, this is the most formal of furisode, and so more than likely can be dropped into the wedding category, more by its general type this time than any specific motif in the design. The argument could also be made, however, that the fan and drum design (note the taiko/drum to the main front left panel) would particularly suit a dancer, who often perform in hikizuri.

This is a hard one to lock down timewise, too. Though its design is very similar to the early Showa ougi furisode above, we can see a visible harshening of the synthetic dyes here, despite the pale turquoise blue and the moss green. Up close there is still a sense of pastel mixes despite its exuberance, but this kimono is no longer trying to imitate the softer and more complex natural plant dyes, and the yuzen work very clean and sharp. The embroidery is also clearly machine-made. It's showing a near-mirror pattern which might be associated with late Taisho, but the ultra-matt quality and weight of the silk, and that more stringent mix of colours, make this far more likely to be a mid-Showa kimono.

When it arrived and I'd taken a little time to look at it, my eyes kept going back to the sleeve length, and to the way that the lower edge of the sleeve hung. The placement of the design there also looked a little off, so after a few days, I pulled out my embroidery scissors and started snikking stiches...and sure enough, there was an entire further 5" of sleeve, hidden inside (not shown on the photo above). Given the length of the furisode, which is short for one of that period considering their trailing nature (the prefix hon- generally identifies a furisode designed to trail its hem), the wearer must have been petite indeed, to the point that it was necessary to shorten not just the body but also the trailing sleeves, to avoid their touching the floor!

They've now been opened back up to their original length, and the fact that the black body of the kimono had no fading has left them no worse for wear, after a little steam and a covered iron. Sourced in Osaka, Japan

Meiji furisode with yuzen. Length: 57"

Possibly the most difficult to photograph furisode in the world, ever!

This Meiji furisode is of a particular orange-red (possibly saffron (beni) dyed) which comes up occasionally, and is universally difficult to photograph with any success by anyone! The silk, which is hand spun and woven, has a certain luminosity which tends to burn out on camera, losing any detail.

It is of a very specific style within its era though, and similar red furisode with this particular colour palette and style of hand painting to the yuzen come up for sale occasionally. I've read before that the style is linked to a specific area in Japan, but have so far been unable to find an example with reliable provenance which would enable me to lock that down.

You can also see that this furisode has had its sleeves shortened to Taisho-length when its owner married, leaving the design sitting a little uneasily there.

We're still in the era where decoration was applied symmetrically, and though you can barely see it even in close shots, this design is linked throughout with very fine, flowing yuzen lines to emulate a stream--another feature often associated with this particular hand-painted style. The lining of this particular kimono has also faded from intense red to a more orange-yellow hue, again suggesting a saffron dye. This furisode is quite thickly padded throughout, with no further thickening to the fukiwata.

In general it's survived quite well, with no stains but a few minor failures to the silk around some of the smaller areas of yuzen (this is characteristic of the stress of yuzen paste work, rather than a shattering of the body of the silk itself). If it were a more recent and so more robust piece I would repair it, but silk of this age tends to be too fragile to support invisible repairs, and even museum mesh would place stress on such a piece, so they become part of the history of this venerable old lady. Sourced in Osaka, Japan.

Karaori furisode with shishu over bokashi shibori. Length: 64"

A heavily embroidered furisode whose padded fuki-wata hints that it may have been intended as a hikizuri. There are several techniques in this piece apart from the heavy embroidery (shishu) to front, back, shoulders and sleeves. The fabric itself is karaori, Kara being Japanese for China and ori for a type of brocade in which extra weft threads in metallic gold or silver are float-woven over a brocade (or plain) background. The technique is more generally seen in obi, as it produces a stiff and heavy fabric--or in its most lustrous forms, in Noh theatre.

Here, it's used as a background for heavy embroidery of sho-chiku-bai in a pastoral setting ( sho-chiku-bai is a Chinese reading of 'matsu' (pine) , 'take' (bamboo) and 'ume' (plum), often referred to as the 'Three Friends of Winter'). Together they represent good fortune, and so are often seen on wedding kimono. In the background silk behind the karaori you can also see dyed bands of turquoise, used to set off the pale gold. It's difficult to specify the technique here, but it's more than likely a bokashi (ombré) dip-dye.

The gold-wrapped thread and the extensive embroidery, along with the weight of the silk necessary to support that, make this kimono heavier than several of my uchikake, despite it being unpadded. Yet the overall visual feel is one of lightness, aided by the paleness of the gold thread against the white brocade. The hakkake is made of the same karaori without embroidery, giving a clear view of the technique. It's interesting that in this furisode the bands of differing gold brocade are offset at irregular intervals across the seams, with only the embroidery matched.

It's difficult to categorize this kimono. At a guess, I would have been tempted to lean towards a wedding kimono, despite its lack of traditional red lining. Its weight was such that I wondered when I first saw it whether it might actually be a wedding uchikake, made to be worn open over a kakeshita, but the existence of a horizontal seam at the waist identifies it as a furisode to be worn with an obi, which would cover the adjustment seam. Although the hakkake is lined with the same material as the outer, as it would be on an hon-furisode, it also lacks padding to either the hemline or sleeves, dropping its standing slightly, although it obviously remains a sumptuous piece intended for a special occasion. Sourced in Kobe, Japan.

Meiji irotomesode with yuzen-moyo and shishu.

An early Meiji irotomesode which, like the blue kakeshita far above, was very likely a furisode that had its sleeves shortened after its owner married, to

enable it to still be worn. It's for this reason that I've placed it here among the furisode rather than among the shorter-sleeved tomesode.

Locking down the time of this type of kimono can be very difficult, as certain styles were popular throughout the late Edo and Meiji periods, even stretching into the beginning of the Taisho period. Tomesode of this style tended to be worn by the Samurai classes, who had conservative tastes and so held on to the sumptuary laws limiting designs to the hemline (suso-moyo). To be safe, I've named this as Meiji.

It boasts a typical design of the time, with small isolated pastoral images to the hemline which are hand-painted, then accented with fine hand embroidery

inside and out, below a bokashi (ombré) dip-dye. This type of gradation is named akebono, and symbolises dawn rising in the painted landscape below.

This kimono is hand woven and hand-dyed shikonzome, which was particularly popular in the Edo period, and a specialty of the Iwate prefecture. Shikonzome lent itself to bokashi dying because in order to gain any strength of violet tone the silk had to be dyed many times over, as the dying agent (the gromwell root), lost its effectiveness so quickly that it would literally lose its pigment as the silk skeins were being introduced, meaning that a strong violet may take fifty or more dips, into fresh pigment each time. The pigment was notoriously uneven for this reason, with the skeins or fabric needing to be pre-dyed before violet was applied, to open up the structure of the silk so that it would receive the maximum dye. In the second picture, showing the tomesode placed over a form, you can clearly see how different skeins of hand-spun and woven silk have taken the dye slightly differently, in the subtle banding of the pigment on the weft (horizontal) thread as it has aged, an idiosyncrasy which separates the plant dye from early synthetic analine replicas.

As is typical of the period, this kimono is padded throughout, with a heavily padded fuki-wara, and no horizontal seam to the rear waistline. Awase (lined) kimono could theoretically be padded and stripped of their padding at different times of year according to the weather, but since this necessitated disassembling the entire kimono each time, wealthy women tended to have dedicated kimono. You can also see that this kimono has no waist seam. This seam, which would normally be hidden by an obi on later kimono, hadn't yet gained across the board acceptance. Tan-mono (fabric bolt) lengths had yet to be standardized to a single longest-length-necessary bolt, so the tuck-seam at the waist which allowed for different heights of kimono to be produced without compromising the design over seamlines, or by being forced to shorten at the hemline, was often not required. These days it's also considered that such a hand-sewn seam, when included, would tend to give at the thread rather than tear the fabric if the wearer were to accidentally step back into the rear of the kimono, or when when sitting seiza, which tends to place a lot of stress on the rear panels of the kimono, both vertically and horizontally (a small panel is generally inserted to the rear of hitoe kimono to reinforce them, as well as provide a guard against moisture transfer). Tomesode of this era were also often layered in colder months, or worn loosely over the shoulders (or even the head) when traveling, which would make such a seam visible, revealing that the bolt had not been laid out and its design spaced specifically for the wearer (a rarity today but more common in the Meiji era and earlier, when high-end kimono were often commissioned from start to finish). Although court tradition of kimono layering in the júnehito fashion was long lapsed save for ultra-formal occasions such as brides--particularly those of the Imperial Household--most high-bred women still chose to wear several layers for formal situations. The remnants of this multi-layer style can still be seen today in the addition of separate eri (collars) or hiyoku (the edges of a supposedly separate layer which is in actuality sewn only to the visible parts of a formal kimono, particularly tomesode).

Although it wasn't unknown for this type of tomesode to be worn layered as a topcoat within the home, the kimono above would have been primarily worn as a

furisode/tomesode with an obi, with or without a trailing hem, indicating the wealth and status of a wearer who seldom had to venture out onto dirty streets. If worn susohiki

(trailing), a shigoki (a long narrow strip of decorated silk) would be wrapped around the hips to hold the trailing hem above the ground outside--the origin of the modern-day ohasori (visible

waist tuck).

This particular iro-tomesode is in great condition with minimal fading and no degradation of the silk, no bleed-through of the bright red lining despite the delicate lilac of the outer silk, and no damage to the white hakkake where it trailed the floor. A lovely example of one of my favorite types of kimono--I only wish I had more! Sourced in Osaka, Japan.

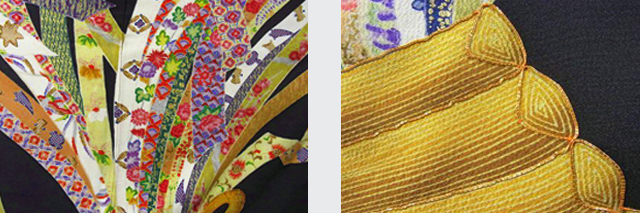

Contemporary furisode with tabane noshi design Length: 64.6"

The dynamic nature of the design is what drew me to this piece, as it generally does with all noshi designs. Tabane noshi originally referred to dried, thin-cut strips of the edible sea mollusc abalone, which were considered a symbol of longevity and so attached to gifts or religious offerings. By the Keichó era, the complex noshi design as we recognize it today had already been set, and real abalone had come to be represented by a strip of straw or yellow colored paper tied in a complex knot.

Because the word noshi also sounds similar to the Japanese word for stretch or progress, a small version of it is also often seen on semori, the charm

embroidered between the shoulders of children's clothing, where the lack of a central seam in the kimono is considered to invite bad luck without something to break it.

The design is often used on adult kimono too, and due to its auspicious roots tabane noshi design furisode often come up as pieces to be worn by both the bride herself and the unmarried sister of the bride at weddings. I have a similar but much less effusive design on a much earlier kuro-tomesode on my tomesode page (click on the blue thre- bar icon at the very top left of this page), probably made for the married sister of another bride, as it's a little too effusive for the bride's mother.

This furisode has a bokashi dip-dye hakkake, as well as bokashi sleeve linings, in this case with the ombré-only part of the lining woven into a damask asanoha design, and the rest of the lining woven as smooth habutae. This mix of damask and plain weaving on a single piece of fabric is something I've not seen very often, and appears to be used solely on contemporary furisode.

Here's the same kimono on a mannequin, which gives some idea of how the design looks when worn, which is always very different.

Many modern kimono designs are printed directly onto a single dedicated bolt of silk using high-end inkjet systems designed specifically for the job, and then given a more sumptuous feel by the use of hand-applied surihaku (gold size work) and kinkoma (gold thread couching). The resulting pieces lend themselves not necessarily to more complex designs than hand-applied yuzen, but certainly to a more intricate nature, as you can see in this furisode. Sourced in Osaka, Japan.

Child's Taisho-era kimono with yuzen, shishu and kinkoma. Length: 38"

The most formal furisode are black with five mon, but whilst colourful iro-tomesode-style girl's kimono are often seen, full black kuro-tomesode styles are a lot rarer. This one has a beautiful design of cranes and matsu (pine) over foaming waves, delicately rendered in yuzen with embroidered highlights and gold kinkoma couching, making it difficult to tie this to either a girl or a boy (sleeve length in antique and older vintage children's kimono were the same for both boy's and girls). Most young boy's formal kimono are of the black-base tomesode style like this one, whilst young girl's kimono tend to be bright confectioneries full of flowers, noshi, temari, fans and other auspicious symbols. However young boy's kimono tend to depict carp, eagles or samurai armor. To me, this kimono has a definite feminine feel to it, so although it's rare to have this kind of more formal tomesode-style kimono for a young girl, I think that's what this is. This subdued five-mon kimono is either for a sichi-go-san (seven-five-three) ceremony, or a family wedding--perhaps both.

The style of crane, the feel of the silk and the lightness of the lining all point this to the Taisho

period. Unfortunately it hasn't fared very well, with the silk deteriorating badly (though not shattering) in the yuzen-painted areas where the rice-paste holdout always weakens its structure,

and around the edges of any embroidered sections for the same reason. It also has prominent age stains to the white cranes. Combined, these flaws reduce it to more of a curiosity than anything

else, but the design itself is wonderfully dynamic, and the sweetness of such a small but serious kimono give it it's own inherent value. Due to their compact size children's kimono always look

particularly appealing when wall-hung, where a full-size kimono needs a large expanse of wall to avoid dominating a space. So despite its poor condition, this one has hung on display in my house

for years, now. Souced in Kyoto, Japan.

Contemporary furisode with hand painted cherry blossom. Length: 62"

Another contemporary furisode, this time with an extravagant design carried out in tones from the

very palest pink to strong but not vibrant brick red. The sleeves are mid-length

here, rendering it to a more manageable chu-furisode. The hand painted design is a wonderful tour-de-force of blossom in every shade of that soft orange-red, making the overall pattern quite

simple from a distance but far more effervescent up close, when the mass of paler blossoms begin to stand out from the pale peach background.

This is an exercise in freehand blossom painting, with no other embellishments such as gold thread or size.

The base silk is a rinzu of stylized blossom within circlets, in ivory with just a touch of pale

peach. The hakkake is a deep brick red bokashi, which probably ties the furisode to somewhere between the 1980's and 2000, when bokashi dip-dyed linings were very much in fashion. After the ultra

pale pastel kimonos of the seventies, we can see color beginning to creep back into more contemporary kimono, a trend that has continued.

Sourced in Kyoto, Japan.

Antique Meiji furisode/susohiki with yuzen and kinkoma

Length: 66"

A Meiji era furisode which was a gift from a good friend. The damask on this particular furisode is

very rich and pronounced, the gloss parts of the fabric reflecting light with a luminosity that only old silk can, making it stunning to look at but hard to photograph. It's also a damask I

haven't seen before, of pheonix and carabana (imaginary

flowers).

In fact the entire colourway is one I haven't seen, with this rather peachy sand tone held out by yuzen against a dark sea blue ground, with fine horizontal yuzen holdout striations either in the silk's original white or in a stronger blush pink, symbolizing haze.

The design itself is more familiar, with young pine trees which have

a small

accent of gold kinkoma sewn to their tips, over distant, haze-covered mountains.

The exceptionally soft silk is not in the best condition, having picked up a few fine insect holes over the years, as well as wear on the folds of the long sleeves, where small amounts of red lining are visible through failures in the outer silk to the very edges of the seams. Hard folding of furisode sleeves to fit them into tatoshi for storage are prone to cause this, particularly if the kimono is not taken out and either hung or reverse-folded occasionally, to ease stress on fold lines. In this case the damage is small and contained, and not visible even on display, and the body of the silk is still strong with no shredding or weakness. The lining is traditional red.

I've listed this as a susohiki furisode, as the length of 66" is extremely unusual for the time, and so despite the quite delicate fuki-wata it must have been intended to trail about the wearer. This isn't a chu-furisode; the sleeves are full-length, designed to reach to just above the wearer's ankle bone, which means that the skirt itself must have trailed. Similar to other Meiji kimono above, a shigoki (a long narrow strip of decorated silk) would be wrapped around the hips to hold the trailing hem above the ground when worn outside; the origin of the modern-day ohasori (visible waist tuck).

Sourced in Osaka, Japan.

Antique Meiji furisode with yuzen

Length: 57"

Here's an unusual early Meiji (possibly late Edo) furisode with its swinging sleeves intact, giving a fascinating insight into the times. If this kimono existed when sumptuary laws were still in place (they effectively ended in the late 1860's, along with shogunate power) then it would have been very close to their end, as the Meiji Enlightenment moved across Japan.

What makes this so interesting is that that we can see the sumptuary laws in action--and being circumvented. The sumptuary edicts were constantly shifting, and this kimono seems to have been made at a time when hand-painted designs were not simply restricted to the bottom of the skirt, but were banned altogether for certain classes.

Whilst the Samurai class were as a rule conservative in their their dress, and it's known that the sumptuary laws were alternately enforced and let slide many times, the type of kimono which was most likely to have had a temporary blind eye turned to such laws was the hon-furisode; the kimono a young woman married in.

So here we see two things. We see the design visible on the outside of the bottom of the sleeves, because after the wedding the sleeves would be cut short as was expected for a married woman, meaning that any design there would be removed. This would have made the kimono suitable for wear as an iro-tomesode (colour-tomesode), with its now-plain design safely within any sumptuary laws.

But we also see something else that was done to get around the law.

Since there were times when even designs restricted to the bottom of the hemline were banned...for a brief time, they disappeared inside the kimono. Women of wealthy families--often in

the lesser merchant class--still wanted their beautiful painted kimono, so if they couldn't have that on the outside, they would hide it within the interior. In this case there's also a tiny hint

of the painted interior on the padded fukiwata (hemline), where you can see the grey of the painted landscape from the interior. Likely you would have seen the barest hint of it as the skirt

flicked with every step, as well.

This became the age of iki; the art of being subtly stylish. It came about as a direct result of trying to circumvent the harsh sumptuary laws, starting in the geisha districts and spreading to town-based merchants, many of whom had become incredibly rich but were held strictly down by the samurai, who were monetarily poorer but still higher up the social ladder, despite often being in dept to the merchants.

So widespread and highly praised did iki become, that it embedded deeply into the country's subconscious and remains even today, in a sense of appreciation of the subtle and the unspoken; of little things that speak volumes.

Why this particular furisode never had its long sleeves cut short we'll never know--perhaps the sumptuary laws had lapsed, and designs were now allowed on the outside of kimono once more--but the fact that they weren't renders it a rare intact example of iki style! Sourced in Osaka.

Hon-Furisode with yuzen, kinkoma, surihaku and shishu.

Length: 66"

An exuberant hon-furisode, probably somewhere between late Taisho and early Showa (1920 to 1940).

This stunning bridal furisode has a design of cranes rendered in yuzen, with several of the main birds embellished with embroidery and gold kinkoma. As with the blue crane hikizuri on my Tomesode page, you can see this style of simplifying the smaller birds so that they fall into the background of the design, though this time many of

the yuzen holdout silhouettes are subtly decorated with individual surihaku patterns applied by stencil.

All this stands over a yuzen rendition of wild waves with high foam, tipped with silver kinkoma. This

wave design continues across the interior hakkake.

The quality of the embroidery is outstanding on this piece, a mixture of sashi-nui (long and short

threads in this case used to define feathers), hira-nui (seen on the crane's head and generally used to fill areas), and sagara-nui (often called French nut stitch, seen in red on the crane's

head). All furisodes tend to be a tour de force of techniques, and here we see near every possible method of applying decoration to a kimono, all to a high standard, combining to render a

beautiful and dynamic design to impressive effect. Sourced in Osaka.

I'm on Etsy!

I've opened a store on Etsy selling vintage kimono and kimono wares from my collection, as well as Japanese cards and gifts handmade by myself from vintage kimono silk. Click on the image above and come take a peek!

Full Wedding Ensemble including Furisode, Red Kakeshita, White Kakeshita, and Alternate Sleeves

Length: 67"

This Showa wedding ensemble is interesting in that it remains intact, including

alternate sleeves for wear post-marriage. It's rare to find a full set like this, as the original full-length furisode sleeves tend to get swapped out and lost, and the less likely to be worn red

and white kakeshita fall by the wayside, particularly as the white silk discolours.

But here we see the full set, plus all their alternate sleeves. The alternate

sleeve trend was a distant relative of the old tradition of cutting short the sleeves of one's furisode after marriage. Here, we see a set which instead includes short and long sleeves for both

the white and the black kimono, so that after marriage a wife could convert her very expensive furisode to a wearable kuro-tomesode, but

still be able to pass the little-worn garment on to her unmarried daughter to be once again worn as a furisode in years to

come.

This is because the original furisode sleeves were not cut, but replaced with short sleeves of matching silk taken from either dividing up a matching tan-mono bolt made and dyed at the time of the original (in which case this plain bolt would serve several sets of sleeves for several kimono ensemble) or from a specialist tan-mono designed with extra length. Such longer bolts were also used to make up longer-skirted susohiki, which require far more silk than any standard kimono.

Here are the detached sleeves of the hon-furisode, with the separate detached sleeves of the white kakeshita just visible to their edges.

The white kakeshita of the set, to be worn under the black furisode above, sports its shorter post-marriage sleeves. It's worth noting that all of the married sleeves in this ensemble are actually of the slightly longer early Taisho-length. None have been shortened further, to the mid-to-late Taisho length. The furisode above also has a matching set of early Taisho-length plain black 'married' sleeves--in fact those sleeves are also attached to their black kimono, with the furisode ones simply positioned over them for the photograph. The white kakeshita is plain white silk, with a lightweight plain silk lining, which really brings home just how many layers one wears with formal kimono, as there would have been a further one, or even two, layers beneath this!

Here's the red kakeshita of this set, which is also awase, with a red silk lining. The outer red silk is rinzu, with a fine, all-over design.

As would be expected, its sleeves are carefully tailored to fit exactly with their

counterparts, so that they can be combined for different parts of the ceremony.

This is the only kimono which has just the one set of sleeves.

The black furisode has its original classic red silk lining, with the outer in a classic black chirimen silk with yuzen and extensive kinkoma, as well as very decorative surihaku and wide-ranging hara-nui embroidery. The design continues on the hakkake (lower lining) as well as both sides of the furisode sleeves, in a stylised waterfall and drum design typical of the period. It has, of course, five kamon, and as with all hon-furisodes, both hem and long sleeves have midweight fukiwata (padding). The set was sourced in Osaka, Japan

Girl's

Taisho summer Ro Chu-furisode

Length: 49.5"

This delicate little summer kimono is beautifully dyed with a soft bokashi blue,

paling to the lower skirt and sleeves for a freehand painted yuzen-moyo design of flowers--probably oleander. Although it has five kamon, its sleeves are a fraction short to be considered full

O-furisode, and the kimono has no padding to either the sleeves or the hem, rendering it to a slightly less formal chu-furisode, though its five mon secure it a place to the top of its

category.

Due to their airy weave ro kimono are delicate things, and fewer survive than the more robust chirimen and kinsha weaves, a fact that is exacerbated by ro kimono's short usage window in the height of summer, meaning that far fewer are bought or made. To find a child's ro furisode is even rarer, since the opportunities to wear this expensive garment are narrowed down further by its formality level, and the child outgrowing any chance of a second opportunity to wear.

Perhaps it's the formality of this kimono which has ensured it has managed to survive in such good condition for its age, since unlike most children's kimono it has remained amazingly free from any specific staining, save a little bruising and general patination due to age.

The ro itself is of good quality, and loose enough in the weave that it may have been hand-woven, though in this instance it's hard to tell. The painting, whilst not the best I've seen, has a delicacy of placement which suits the ro very well, the space around the design as important as the image itself in lending that all-important sense of cool airiness. It's this which, in this instance, gives this small kimono a cheerful, heartwarming, and gently ephemeral sense which so effortlessly epitomizes the long, warm days of childhood summers, to always makes me smile.

Sourced in Kyoto

Don't forget you can navigate between pages by clicking on the small blue three-bar icon at the very top left of this page - other pages and subjects will appear.